A synthesis

In the lesson Our perception of being I I concluded by saying that the ego can be conveniently regarded as a spiritual experience. I think we can push beyond this language and say that the self is spirituality, I am spirituality, what essentially is valid in me is the spiritual experience of this “me” that I can carry on. This so important experience risks always vanishing, being attacked by everything that in and out of me conspires and militates against it, not excluding our temptation of absolutizing it, with the result of depriving it of what different it needs to get rich of the most profitable balances. Therefore, before worrying about making spirituality exist in this world, I should make it existing in me, in order not to talk about something that I myself don’t know. For this reason the obvious necessary practice is silence, however it is organized and managed.

This warning against the world of distractions and our call to silence lead us to think of a way of hermitage, but today it can no longer be guided by peaceful images of a monastery or hermitage. It has necessarily to be a suffered hermitage, a cross, a living never pleased with itself, a hermitage that will never give up seeking the other person, because the other’s conscience, no matter how flawed, even with all its being evil, its being universal and not human spirituality, is still necessary so that my spirituality is not reduced just to complacency.

In this sense our need to exist in the consciousness of others should be exploited and managed as an opportunity for enrichment that is such that even in the midst of the deadly imbalances of others. The other person kills me all the time, but without her killing me, or if I react to her killing me without a critical and self-critical walk, I can only exist as a spiritual vacuum. This comes out as a response to Sartre, who said that hell is other people.

In other words, we can deduce that, once in this world there is the deadliness of the existence of others, Jesus could not make to exist in the world any worth considering spirituality but by addressing face to face this deadliness. Here it emerges a sense of the story of Jesus not as a victim but as a I-spirituality that couldn’t have realized itself without the spirituality of others, although these others killed him.

In other words, Jesus’ death was not the last word, but it is only part of a dialogue, albeit dramatic, where the culpability of those who killed him is still waiting for more answers; we wonder not only why Jesus had to die, but also why his killers could not escape their own decision to kill him. That means taking seriously the exclamation “forgive them for they do not know what they do” Luke 23:34, a forgiveness that does not solve the problem.

We understand that a discussion of this kind is for advanced people, people who have had the opportunity to experience the greatness, the critical consistency and the attractiveness of a human spiritual experience. In this context I disagree with Levinas’s approach, who instead considers the other in a perspective that seems to me too optimistic, after all visionary about good in people, not putting due emphasis to the deadliness, to which on the other hand the murderers themselves cannot escape and that the drama of Jesus laid bare.

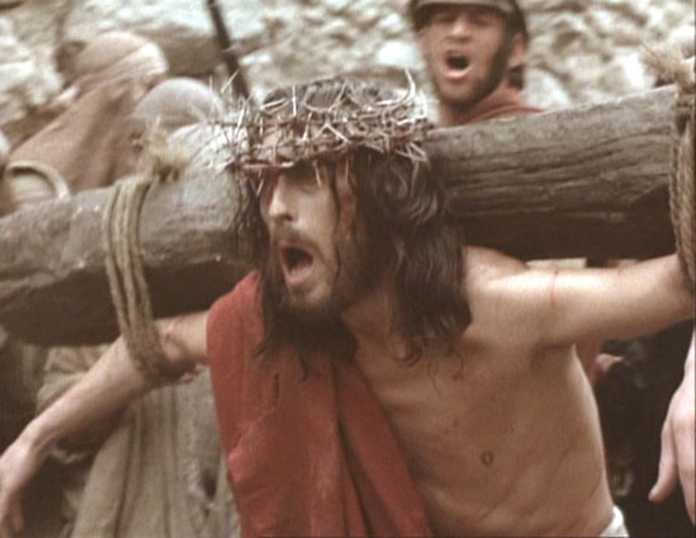

In the course of our being dying people (which means that our walking is continuously killed, but we ourselves go in search of our killers) our response should be to continue, in any way, to facilitate walking and make it to exist, along with the spirituality that through it makes its way in us. In this sense it becomes important the image of Jesus who goes to Calvary to be crucified: he carries the cross, but it is important that he carries it by walking, showing, among other things, that the standard of walking is limping, falling, recovering, failing, having a poor show with others and with ourselves.